Sure, we love plants for their beauty and fragrance, but have you ever browsed the aisles of your local garden center and felt your creative side, I don’t know, sigh just a little? That’s a huge problem: settling for the tried-and-true when you’re really craving weird, funny-looking plants that belong in a school science fair.

But committing to adventure often leads to disappointment. Either you can’t find a place to buy the weird plants you’re looking for, or the plant is too temperamental for the average gardener.

But all hope is not lost! With a little work, anyone can grow these out-of-the-ordinary plants at home.

On This Page

Giant Allium

Allium giganteum, Zones 4 to 8

It’s not just the umbel of star-shaped flowers that make the giant allium a showstopper, it’s the sheer size of this bulbous perennial. The deep purple blooms are 5 to 6 inches in diameter, and the stems reach a height of up to 50 inches, giving the summer bloomer a serious wow factor.

Why we love it: The height makes it an ideal filler (or thriller!) at the back of the garden bed.

Prairie Smoke

Geum triflorum, Zones 3 to 7

This late-spring bloomer thrives in woodland and wildflower gardens. Clusters of reddish pink, maroon or purple flowers with fused sepals bloom in groups of three. The flowers are followed by fluffy seed heads in shades of silvery pink. In the fall, the semievergreen leaves turn red, orange or purple.

Why we love it: A native North American perennial, prairie smoke is said to have medicinal properties.

Snake’s Head Fritillary

Fritillaria meleagris, Zones 3 to 8

In April, the low-maintenance bulb produces delicate blossoms on slender stems. The bell-shaped blooms boast a checkered pattern in reddish brown, purple, white and gray shades. The pattern pops when the bulbs are planted in clusters.

Why we love it: This low-growing perennial is deer resistant, making it an excellent spring bloom.

Candy Cane Sorrel

Oxalis versicolor, Zones 7 to 9

The swirls of red and white on the bud of this festive flower mimic the colors of a candy cane. The buds unfurl during sunny weather to reveal white petals rimmed in red. The plant grows well in full sun, and the blooms last from midsummer through fall.

Why we love it: Watch this plant thrive in a container and even as a houseplant.

Elephanthead Lousewort

Pedicularis groenlandica, Zones 2 to 7

Purplish leaves appear after the snow melts, and soon after, it produces pinkish purple petals that resemble an elephant’s head. The perennial grows up to 2 feet tall, and although it can be a challenge to grow, the flowers are a great source of pollen for bees.

Why we love it: With a native habitat at high elevations, it’s ideal for northern gardens.

Firecracker Flower

Dichelostemma ida-maia, Zones 7 to 10

Red, pink or green flowers grow in clusters resembling their namesake with fuses attached to the stems. The herbaceous perennial is native to Oregon and California, where it’s abundant in woods and coastal grasslands. It grows up to 3 feet tall and blooms from May through July.

Why we love it: A favorite of hummingbirds and bees, it tolerates poor soil, shade and drought.

Red Hot Poker

Kniphofia, Zones 5 to 9

Flowering spikes bursting with tubular florets add plenty of drama to any collection of weird plants. The flowers appear in late spring through summer on tall spikes over grassy foliage. Native to southern and eastern Africa, red hot poker thrives in full sun and hot climates.

Why we love it: Different varieties have varying shades of flowers, from cream and yellow to orange and red.

Grape Hyacinth

Muscari paradoxum, Zones 5 to 8

An heirloom classic, grape hyacinth is a perennial favorite. The first flowers appear in March and become spikes bursting with blooms that last through May.

Why we love it: Beautiful and fragrant, it is an early spring favorite of pollinators.

Gloriosa Lily

Gloriosa superba, Zones 8 to 10

The national flower of Zimbabwe, gloriosa lily grows best in temperate and tropical climates, but it can also be grown as a summer bulb in colder areas or in containers where weediness or invasive potential is a concern.

Why we love it: The slender stems and tendrils are great at climbing walls or trellises, reaching lengths of up to 15 feet.

Polka Dot Begonia

Begonia maculata var. wightii, Annual

An impressive height of 3 to 4 feet provides a good view of this begonia’s striking leaves. The elongated-heart shape and ruffled edges make for lovely foliage, but the round, sparkly white spots steal the show.

Why we love it: It’s not just beautiful—it’s a brilliant example of nature’s engineering. It is believed that the spots scatter sunlight within the leaves, helping this begonia adapt to lower light below a forest canopy.

After you read our list of weird plants, check out more fabulous foliage plants for garden pizzazz.

Sea Holly

Eryngium, Zones 5 to 8

Like the coneflower, sea holly is a relatively hardy perennial, sporting a central head ringed with a ruff of “petals.” Except these aren’t petals, but bracts that also sprout out along the stem. And the cone is covered with individual, fully functioning flowers, complete with male and female parts.

Why we love it: Sea holly is the Dr. Jekyll to coneflower’s Mr. Hyde, with its spiky bracts and eerie metallic hue.

Artillery Plant

Pilea semidentata, Zones 11 to 12

It’s easy to grow this compact perennial indoors near a window or outdoors on a bright patio. With tiny green leaves on multiple stems, the artillery plant offers a pleasing mound of green year-round. Periodically, flat-topped inflorescences appear, tipped with tiny reddish buds. Watch carefully as they plump up.

Why we love it: Mist those fattened buds and wait about 30 seconds. Poof! Whoof! Puffs of pollen begin bursting out as the flowers open, wafting up like smoke from a cannon.

Check out 10 seriously cool succulents that make great houseplants.

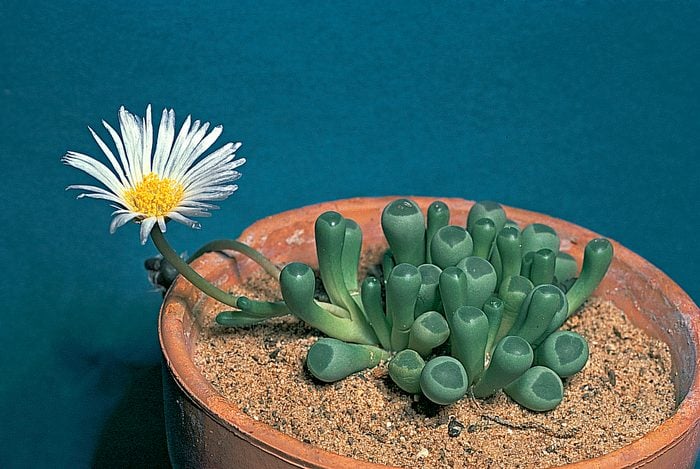

Baby Toes

Fenestraria rhopalophylla, Zones 10 to 12

Like other window-leaved succulents, this one has chubby leaves tipped with triangular patches of translucent pigment. The windows protect these weird plants from burning desert rays while letting in just enough light for photosynthesis. A large white flower rises up from the sand to attract pollinators.

Why we love it: In bright light, baby toes produce a red pigment that gives them further protection from the sun. They take on a pink tinge, almost seeming to blush.

No green thumb? Try the top 10 hard to kill houseplants.

Spider Orchid

Brassia, Zone 12

To me, it looks like a skinny starfish on a stalk. But to wasps, the five banded petals of this tropical orchid resemble big, tasty spiders. While wrestling with the blooms, a wasp becomes covered in pollen, which it will helpfully—though hungrily—take to the next spider orchid.

Why we love it: When it comes to botanical moxie, it’s hard to beat a wasp-wrangling orchid.

Here’s our complete guide to growing orchids.

Sensitive Plant

Mimosa pudica

With delicate powder-puff flowers and lacy fernlike leaflets, the sensitive plant seems to earn the name pudica—shy—based on appearance alone. But touch it gently and the leaves fold up, one pair at a time, all the way down the axis.

Why we love it: Within 15 to 20 minutes, the leaflets open back up. It’s hard not to admire such resilience.

Tarantula Cactus

Cleistocactus winteri, Zones 9 to 11

In its native Bolivia, this cactus creeps along the rocky ground—but in a tall pot, its stems bend to resemble an enormous, hairy spider emerging from its hole. Just when you get super creeped out, pretty salmon-colored flowers bloom.

Why we love it: With regular water and fertilizer, it can grow several inches each year, making this one of our weird plants more fun than horrifying.

Black Tree Aeonium

Aeonium arboreum ‘Zwartkop’, Zones 9 to 11

Tight rosettes of leaves high atop narrow, gently crooking stalks: Even without the murky coloration, the black tree aeonium smacks of the Gothic. But this perennial craves bright light and warmth, so be prepared to bring it indoors for winter.

Why we love it: Black tree aeonium doesn’t bloom easily, but when it does, the breathtaking contrast of yellow flowers against the dark leaves makes all the effort worthwhile.

Like the dark side? Don’t miss the top 10 black annual and perennial plants.

Porcupine Tomato

Solanum pyracanthum, Zones 9 to 11

It starts out innocently enough, a 2-foot-tall plant with elegant lobe-shaped, gray-green leaves. Then—bam!—bright spines start popping up through those leaves. The leaf tops, the undersides, the stems and even the fruit sport these pointy prickles. Note that all parts of these weird plants are poisonous.

Why we love it: Petals usually get all the points for prettiness, making porcupine tomato (also known as devil’s thorn) a lovable, although far from huggable, underdog.

Sources

- Timber Press Bizarre Botanicals by Larry Mellichamp and Paula Gross

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension, Prairie Smoke

- North Carolina Cooperative Extension – Giant Allium

- Missouri Botanical Garden – Snake’s Head Fritillary

- North Carolina Cooperative Extension – Gloriosa Lily

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension – Gloriosa Lily

- North Carolina Cooperative Extension – Firecracker Flower

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – Firecracker Flower

- Missouri Botanical Garden – Red Hot Poker

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center – Elephanthead Lousewort

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

While other woodpeckers hammer out their meals from trees or buildings, the Lewis’s woodpecker employs a more graceful yet nontraditional technique. “They catch insects on the wing,” says wildlife biologist Kaly Adkins, who works with the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife. “They are super fascinating because they feed like a flycatcher and fly like a crow.”

On This Page

What Does a Lewis’s Woodpecker Look Like?

With its slow wing beats and long glides, this 10-to-11-inch-long bird might be mistaken for a crow or jay until its beautiful coloration is visible. “They have brilliant, iridescent colors,” Kaly says. “There is black and green plumage on their back to blend in with burnt trees. And they are cute with those pink bellies.”

Males and females look alike, although the males are slightly larger. Both share the black bill, gray collar and red on their faces, as well as relatively long wings and tails.

Lewis’s woodpeckers were described by, and later named for, Capt. Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark expedition who observed them in 1806 in western Montana. The species was initially known scientifically as Picus torquatus, meaning “woodpecker with a necklace.”

Nesting Habits

Lewis’s woodpeckers lack the heavy skull structure of other woodpeckers and are predominantly secondary cavity nesters in decaying trees, which is one reason it’s beneficial for homeowners in their range to allow standing dead or decaying trees to remain whenever possible.

“They recycle a lot of flicker nests,” Kaly says. Lewis’s woodpeckers nest between mid-April to early June. They sometimes expand the cavity and line it with bark chips, where they’ll raise one clutch with five to nine eggs. Both parents incubate the eggs and care for the young.

What Does a Lewis’s Woodpecker Eat?

Lewis’s woodpeckers are omnivores, but their eating habits focus on what’s available. In their range, which covers areas in the western half of the U.S. and expands into British Columbia, they focus mainly on insects in the warmer months, sometimes adding fruit to the menu. They gather and store acorns and nuts in tree limb crevices for later use when insects are not prevalent.

Unlike other woodpeckers, Lewis’s often perch on a branch and swoop after flying insects.

“Flycatching from atop a 100-foot snag on the shoulders of Mount Jefferson in Oregon, the aerial maneuvers of Lewis’s woodpeckers are stunning. The iridescent green, black, red and silver colors make the Lewis’s an outstanding resident of central Oregon and the Cascades. This particular woodpecker (above) was enjoying bugs after a burn,” says Birds & Blooms reader Douglas Beall of Camp Sherman, Oregon.

Migration and Range

“For many species, migration is well defined, but we know Lewis’s woodpeckers are more versatile in their migration strategy,” Kaly says. In the fall some Lewis’s in the northern range migrate south, while others, particularly in temperate areas along the West Coast, remain in their home range the entire year.

There’s a strong connection between these woodpeckers and wildfires in their range: The open post-fire landscape often means more aerial hunting opportunities. Plus, standing dead trees provide important nesting opportunities for them.

Sound and Calls

Bird songs courtesy of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

About the Expert

Kaly Adkins is a wildlife and conservation biologist who works with the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife. Kaly has also studied movement and activity of rare Sierra Nevada red foxes, bats and wolverines.

Sources

- Joint Fire Science Program – Fire Science Brief

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Washington NatureMapping Foundation

- Lewis & Clark Trail Heritage Foundation

- eBird

- U.S Geologicial Survey – Mount Jefferson

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

One of the joys of spring and early summer is the sheer abundance of bird songs filling the outdoors. Every kind of bird adds to the chorus with its own particular sounds—often beautiful, sometimes harsh, but always interesting. It’s possible to enjoy this free concert for its musical quality, but it becomes even more fascinating when we know why the birds make these sounds.

On This Page

Bird Songs or Calls: What’s the Difference?

Most common backyard birds make a variety of sounds, including songs and calls. For example, the American robin song is a rich, whistled caroling—chirrup, cheerio, cheerup, cheerily—often beginning at dawn or even earlier. Robins also make many different calls, including low clucks and chuckles, sharp cries and thin lisping notes.

Songs are typically longer and more complicated than calls, and may be more musical. But the main difference is in their purpose.

You can hear calls at any time of year, and they have a variety of functions. Harsh notes may serve as alarm calls, and the birds may have different alarm notes for various threats. Sometimes short, simple calls help members of a flock stay in contact with each other. Young birds often have food-begging calls, different from any sound made by the adults, to let their parents know when they are hungry.

Songs, on the other hand, are performed mostly by adult males, and they use them to lay claim to a nesting territory and to attract a mate—or to communicate with their mate after they have paired up. So almost all the singing is during the breeding season, and the symphony ends around the time the last brood of fledglings is ready to leave the nest. When the birds sing at other times of year, they may simply be practicing.

Learn how to identify birds by their song.

How Do Birds Learn to Sing?

Songbirds perform so naturally that we might imagine they were born knowing their tunes, but most birds actually have to learn them. If they don’t hear their own species’ song while they are young, they will never learn to sing it properly. And because they learn to imitate the songs they hear in their home area, some species develop regional song dialects, like how humans from different places speak with varying accents.

Bird mimics and mimicry: here’s what you need to know.

White-crowned sparrows and mourning warblers are examples of birds with distinctive local dialects. But calls, unlike songs, seem to be instinctive, and birds develop the typical calls of their own species without having to hear them first.

Members of the flycatcher family, such as the eastern phoebe and great crested flycatcher, differ from other songbirds because they develop their songs through instinct, not learning. And because many species of flycatchers look very similar to each other, it’s imperative for them to be able to recognize their own kind by voice.

For groups such as hawks, geese and ducks, all vocalizations are calls, not songs. And some other bird groups don’t fit in the songbird category but still make sounds that function as songs, including some hummingbirds and many nocturnal birds such as owls and whip-poor-wills, singing in the dark to defend their nesting territories. These birds are all thought to develop their sounds through instinct, not learning.

Music in motion: meet the birds that sing while flying.

Do Female Birds Sing?

For many years, scientists assumed that males were the only important singers among birds. But recent studies have changed that view. Singing by female birds has been documented in hundreds of species now, with new examples being discovered all the time.

Female northern cardinals sing musical, whistled songs like those of the males, although not as often. In tropical forests, many female birds sing regularly, and the male and female of a pair may sing duets back and forth. Wherever you are, some birds are likely to be performing free open-air concerts nearby. Take the time to listen, and you’ll be treated to some of the most fascinating sounds in nature.

Hear the soothing sounds of a mourning dove call.

Why Do Birds Sing at Dawn?

During late spring and early summer, an incentive for waking up early is the chance to hear the dawn chorus of bird songs. Some birds, such as robins and cardinals, may start singing when there is just a hint of light on the eastern horizon. More birds join in as dawn approaches, with a peak of song right around sunrise.

Why do they start so early? Birds may need to assert their claims to their nesting territory first thing in the morning, just in case any migrants have arrived during the night. And singing may be the best use of their time when it isn’t light enough yet to search for food.

Next, learn what a Baltimore oriole song sounds like.

About the Experts

Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman, authors of the Kaufman Field Guide Series, are the official birding experts for Birds & Blooms.

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

American robins are commonly spotted (and heard) in backyards throughout most of North America. Watch for robins in your yard, no matter what the weather is like. Find out what foods robins eat and how to attract these birds throughout the year.

Learn all about robin nests and eggs.

On This Page

Do Robins Eat Bird Seed?

Robins are not seed eaters, so you won’t attract them with seed bird feeders. Instead, look for them on the ground. Every child knows that robins eat worms. But they also eat lots of other things, too like insects, grubs, and even snails. We tend to notice them around our gardens because they hunt for these things on the ground.

The next time you observe an American robin in your yard, notice how they curiously tilt their heads. They do this to listen for juicy worms. Robins use both visual and auditory clues to hunt down their favorite slimy snack.

Robins also eat fruit, which they search for in trees and shrubs—not where we’re used to seeing them. When winter comes, the worms and insects aren’t as available to them, so during the cold months their diet consists mostly of fruit.

What’s the difference: European robin vs American robin.

How to Feed and Attract Robins in Winter

As the ground thaws and worms break through the surface, robins, members of the thrush family, become more active and visible again. But you can attract robins to your yard even when it’s snowing. In winter, flocks of robins gobble up berries from shrubs and trees. You can attract robins to your yard with trees that bear fruit in winter such as chokecherry, hawthorn and dogwood.

You can also create small piles of leaf litter around your yard to attract robins. According to the National Wildlife Federation, leaf litter is a natural habitat for insects, which in turn provides a backyard dining spot for grub and insect-eating birds such as robins.

How to Attract Robins to Feeders

“A flock of robins stayed with us last winter and ate all the berries growing in our area. How can we attract them to feeders?” asks Birds & Blooms reader Susan Petrch of Millbrook, Ontario.

Birding experts Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman say, “Robins aren’t typical feeder guests, but there are some things you can try. It’s best to place an open tray feeder near one of the berry-producing trees frequented by the robins and stock it with raisins, apple slices or other fruit. You can also offer mealworms or suet.

But it’s normal for flocks of robins to be nomadic in winter, wandering long distances and stopping when they find a natural food source. Once they’ve depleted the local berry supply, most likely they’ll be off in search of the next berry crop instead of sticking around at feeders.”

Did you know: Robins also visit bird baths for fresh water. You can offer a heated bird bath in the winter to bring these birds to your yard.

Enjoy cheerful robin bird pictures to welcome spring.

Do Robins Eat Suet?

“Is it uncommon for robins to like suet? I’ve had one visiting my feeder twice a day,” asks reader William Toth of Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania.

Kenn and Kimberly say, “Although people tend to think of robins as strictly worm eaters, they actually have quite a varied diet. Wild fruits and berries make up a big part of their diet, especially in fall and winter, when worms are much harder to come by. Robins are not commonly attracted to feeders, but sometimes an individual will key in on a feeder offering mealworms, raisins, suet or even grape jelly, and will start visiting it regularly.”

Next, find out if robin sightings have special meaning.

Additional reporting by Kirsten Schrader

About the Experts

Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman, authors of the Kaufman Field Guide series, are the official birding experts for Birds & Blooms.

Sources

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

On This Page

Why Groundhogs Are a Problem in the Garden

Perhaps most famous for having a February holiday named after them, groundhogs are furry mammals that can be found across much of the eastern and central U.S. and up into Canada. Groundhogs create deep underground burrows, some of which stretch for more than 20 feet. These rodents aren’t particularly picky eaters, happily snacking on a wide range of vegetation including grasses, bark, flowers and berries.

Did you know: Whether you prefer to call them groundhogs or woodchucks, it’s perfectly fine to call these animals either name.

The problem comes when they move into backyards and start devouring your garden plants. Groundhogs like to pack on pounds during warmer months to gear up for hibernation, which typically starts in mid-fall.

Read on for expert and home gardeners’ advice on how to keep groundhogs out of your garden.

Will Gopher Spurge Deter Groundhogs?

Birds & Blooms reader Linda Hall of Aurora, Indiana, asks: “A groundhog loves eating my mums. Can I plant something nearby to discourage it?”

“Unfortunately, no plants can actually deter groundhogs from eating flowers or shrubs,” says gardening expert Melinda Myers. “You may have heard rumors that gopher spurge (Euphorbia lathyris) repels gophers and moles. This hasn’t been proven to be true. This spurge is very aggressive, reseeds readily and is considered invasive in a few states.”

Use Fencing to Keep Groundhogs Out of Gardens

Melinda points out that using fencing to deter groundhogs is challenging. They are extremely versatile and can both climb and burrow. Bury the bottom of a fence at least a foot deep or bend the bottom foot of fencing at a 90-degree angle and pin it to the ground. The fence needs to be 3 feet high, with the top 12 to 15 inches bent outward at a 45-degree angle to help keep groundhogs from climbing it.

An electric fence mounted on posts with strands 4 inches and 9 inches above the ground is another option that is probably more effective. Look for electric fences at garden centers or online.

Reader Ideas to Deter Groundhogs and Chipmunks

Home gardeners share their favorite techniques for keeping groundhogs and chipmunks out.

- I try to find the groundhog’s home (usually under my shed or deck) and have used a flood light and music as a deterrent under the deck. I’m not sure which worked, but the groundhog and its family left, says Field Editor Boni Trombetta of West Chester, Pennsylvania.

- To keep chipmunks from eating the roots of my potted plants, I put small flat stones on top of the soil, says Monica Partington of Raleigh, North Carolina.

- Vinegar can help keep away critters. You have to apply it often enough that the scent stays detectable by humans (and therefore stronger to the animals), says Field Editor Kathryn Rucci of Orlando, Florida.

- I scatter my husband’s hair around the garden after giving him a cut, says Char Jasinski of New Berlin, Wisconsin.

- To prevent them from eating my lettuce, carrot tops, beet greens and more, I make hoops and cover them with bird netting. They get the hint, says Field Editor Sue Gronholz of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin.

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

Sources

- North Carolina State Extension

- Melinda Myers, official gardening expert for Birds & Blooms

On This Page

What Does a Domestic Mallard Look Like?

“This large duck hangs out with mallards but looks completely different. What is it?” asks Birds & Blooms reader Todd Gorski of Mishawaka, Indiana.

Birding experts Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman say, “Most domestic ducks are descended from the mallard, first domesticated in the Far East more than 2,500 years ago. Many distinctive forms have been selectively bred for new colors and sizes. These are not separate domestic duck species, just different varieties, much like there are many breeds of dogs. These varieties all interbreed with each other, producing intermediates.

More than 80 mallard varieties have been named. Some are large and dark with a white bib, such as the bird in your photos. Your bird doesn’t seem like an exact match for any named breed, but it’s similar to both Duclair and Blue Swedish ducks.”

What foods can you feed to ducks?

Escaped Domestic Ducks

“We saw these ducks (above) while at the Sacramento National Wildlife Refuge Complex last October. What kind are they?” asks Roy and Debbie Pardee of Ukiah, Connecticut.

Kenn and Kimberly say, “The short answer is that these are escaped domestic ducks, but the long answer is more interesting. Most domestic ducks are descended from either mallards or Muscovy ducks, and those in your photo are in the mallard line. Over the last several centuries, people have developed many distinctive breeds of these ducks, ranging from all white to glossy greenish black, and many colors in between.

These two look most similar to a rare breed called the Ancona duck, but they are not completely typical. When domestic ducks escape from captivity, they may wander in the wild for years, causing confusion for bird watchers.”

Meet 20 types of ducks you should know.

Are These White Mallard Ducks Leucistic?

“I saw these ducks while in Gilbert, Arizona. I think they’re leucistic mallards, but my dad thinks they’re a different species. What are they?” asks reader Elsa Papenfuss of Star, Idaho.

Kenn and Kimberly say, “Mallards have been domesticated for more than 2,000 years, and many distinct breeds have been developed during that time. These are not separate species, just varieties, comparable to dog breeds like poodles or beagles. More than 80 varieties of domestic mallards have been recognized and named, and because they can all interbreed with each other, they produce many intermediate forms. The birds in your photo look similar to a couple of types called Blue Swedish and Ancona, although these ducks aren’t quite typical for either.”

Domestic White Crested Duck

“This photo was taken at a lake in Columbus, Ohio. Can you tell me what kind of duck this is?” asks reader Georgette Ingellis of Bristol, Connecticut.

Kenn and Kimberly say, “Over the centuries, waterfowl breeders have developed many distinctive varieties of domestic ducks, with almost all of them descended from the familiar mallard. This attractive breed is called a white crested duck. It has been a recognized variety for more than 300 years, with ducks of this type seen in Dutch paintings of the 1660s. Like other domestic duck breeds, white cresteds are sometimes seen wandering around in the wild or visiting park lakes.”

Learn how to identify a wood duck.

Domestic Hybrid Canada Goose

“I saw this goose in a group of Canada geese and noticed that it was different. What kind is it?” asks reader John Yinger of Columbus, Ohio.

Kenn and Kimberly say, “Interesting goose! It looks like a hybrid—a cross between a Canada goose and a domestic greylag goose. This kind of thing happens occasionally, because geese are not always very picky in mating season. Canada geese are often involved in these mixed pairings. The trick is to figure out the identity of the other parent. For the bird in your photo, the overall body color, large pinkish bill and heavy rear end all suggest that a domestic greylag was the other member of the pair.”

Next, learn how to tell the difference between a canvasback vs a redhead duck.

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

On This Page

Forsythia Bush Growing Tips

- Common name: Forsythia

- Scientific name: Forsythia spp.

- Zones: 4 to 8

- Light needs: Full sun

- Size: 8 to 10 feet high; dwarf varieties are available

- Grown for: Sunny yellow flowers

- Foliage: Dark green leaves

When a forsythia bush (Forsythia spp.) blooms, it’s a sure sign that warmer weather is on the way. Forsythia is one of the earliest bushes to bloom in spring, making its bell-shaped golden flowers a welcome sight.

Forsythia is a fast-growing, large shrub that thrives in Zones 4 to 8. (Here’s how to find your plant zone). It will grow to be 8 to 10 feet high, though there are dwarf varieties available and it can be pruned for size. Give this plant a try as a hedge that’ll put on a spectacular show in the spring.

For best results, grow forsythia in well-drained soil with regular moisture and in full sun to part shade.

When Does Forsythia Bloom?

Forsythia can bloom as early as late January or early February in warmer zones. It’ll bloom through late March in colder zones. The sunny yellow blooms last for 10 to 14 days. After the flowers fade, dark green leaves emerge.

Blooms develop in late summer and early fall for the following year, so the shrub should be pruned immediately after flowering in the spring for best results.

Check out the top 10 flowering bushes for your yard.

Forsythia Bird Benefits

Place seed feeders near forsythia and other shrubs so birds can wait their turn for a snack or safely hide from backyard predators.

Check out the top 10 trees and shrubs with berries for birds.

Why Is My Forsythia Bush Not Blooming?

“My forsythia had flowers for the past two years, but only on the bottom of the shrub. What’s wrong with it?” asks Birds & Blooms reader Janet Grosse of Madison, Wisconsin.

Horticultural expert Melinda Myers weighs in: “This is a common problem for those of us growing forsythia in colder climates. Even though the plant tolerates the winter cold, the dormant flower buds that form during the previous summer are often killed.”

Melinda has recommendations for cold-hardy cultivars that’ll thrive in areas with more intense winters: “In the future, select forsythia cultivars, such as Northern Sun, Show Off Starlet, Gold Cluster or Fiesta. They all have hardy flower buds that can withstand colder weather,” she says.

You can try other cultivars to fit your needs, too. Northern Gold is an upright grower and Meadowlark is fast-growing with an arching form. For a cultivar that’ll thrive in warmer climates, opt for Spring Glory.

Forsythia Bush Facts

- Originally called Syringa suspensa, the first identified forsythia species was renamed after Scottish botanist William Forsyth in 1804.

- Ready to make a statement? Meadowlark forsythia can reach up to 10 feet high if unpruned.

- All varieties of forsythia share the same characteristic four petals.

- Forsythia flower buds begin to drop if temperatures hit minus 5 degrees. Look for “flower-bud hardy” types for the most reliable flowering in colder areas.

- There are about 11 species in the Forsythia genus, which falls under the olive family, or Oleaceae. They all hail from Asia except for one from Europe.

- Like lilacs and crabapples, forsythia branches will flower early in a vase indoors—for an average of two weeks—if cut while budding.

Additional reporting by Erica Browne Grivas

Reviewed by horticultural expert Melinda Myers

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

Sources

- University of Oxford

- Missouri Botanical Garden

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Division of Extension

- The Royal Horticulture Society

- North Carolina Cooperative Extension

How to Stop a Bird From Pecking at a Window

“A cardinal is pecking at my window constantly. How do I make it stop?” asks Birds & Blooms reader Kay Baker of Mercer, Pennsylvania.

Birding experts Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman say, “When a bird starts pecking at a window like that, it has mistaken its own reflection for another bird and is trying to drive it away. Some individuals become obsessed with these phantom rivals and may attack them for weeks.

The only real solution is to do away with the reflection itself. You need to block the reflection on the outside of the glass. Putting an exterior screen on the window is one simple solution. If that isn’t possible, try rubbing a bar of soap on the outside of your windows in all the spots that the bird visits regularly. Or tape a piece of paper or plastic over those areas. If none of those options are feasible, you can just wait.

The cardinal should lose its drive to defend its territory after the breeding season wanes. Even if you can’t block all the reflections, this behavior should end after a few weeks.”

Find out why woodpeckers peck and how to stop it.

Birds Pecking at Car Mirrors

“Why do cardinals peck at my vehicle’s side mirror?” asks reader Patricia Ekakiadis of Avonmore, Pennsylvania.

Kenn and Kimberly say, “Cardinals, like many other birds, defend a territory during the nesting season to make sure they have enough space and food for themselves, their mate and their young. If a male cardinal sees another male cardinal in his territory, he chases the trespasser away.

Unfortunately, he can’t tell the difference between a real cardinal and a reflection in a mirror. So he might spend hours trying to chase away this false intruder that can’t be intimidated. You might try covering the mirror when you’re not driving your car so this defensive cardinal can go about his business.”

Are hummingbirds territorial at feeders and flowers?

About the Experts

Birding experts Kenn and Kimberly Kaufman are the duo behind the Kaufman Field Guide series and speak and lead bird trips all over the world. If you have a bird-related question for them, submit it here! It could appear here or in a future issue of the magazine.

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.

On This Page

What Does a Rivoli’s Hummingbird Look Like?

An adult male Rivoli’s hummingbird has that classic hummingbird shimmer, but they’re even more dazzling than many of the other types of hummingbirds in the United States. A teal green gorget and purplish feathers on the crowns of their heads are a surefire way to identify a male. The feathers on his back might appear black, but take a closer look—they’re an iridescent dark green.

Telling a female Rivoli’s apart from other species is a bit trickier. At first glance, she bears a close resemblance to several other juvenile or female hummingbirds. Take note of the second, defined white stripe branching from her bill to the area just below her eye and the green feathers on her back as keys to correctly identify her.

Another easy way to differentiate between Rivoli’s and many other hummingbird species is to note their size. Of identifying a Rivoli’s, Audubon Southwest’s Director of Conservation Tice Supplee says, “The first clue is ‘He’s big!'” She explains that a Rivoli’s hummingbird is about three times the size of a black-chinned hummingbird, and two and a half times the size of a ruby-throat.

Attract hummingbirds to your yard with proven tips from birding experts.

Range: Where Do Rivoli’s Hummingbirds Live?

If you’re determined to spot a Rivoli’s, you’ll need to head south. These gem-colored little fliers only enter the United States during breeding season. They buzz over to mountainous areas in the Southwest, and specifically in lower Arizona and New Mexico. You might find one on the far west side of Texas during breeding season as well, but you’d have to be pretty lucky—those sightings are uncommon.

“What we have in the U.S. is a breeding population,” Tice explains. “When you get into Mexico, Costa Rica and Nicaragua, they have them year-round.” Tice also mentioned that the birds tend to migrate each year to the sky island mountain ranges in Arizona and New Mexico.

Interestingly, she also mentions their range might be expanding. “Records are starting to show up further north,” Tice says. “There’s a breeding pair now that’s reliably seen in Oak Creek Canyon in Sedona, Arizona, so that’s pretty far north.”

Rivoli’s Hummingbird Diet

With such a limited range, Rivoli’s hummingbirds aren’t typical backyard birds. That said, those living in the area they migrate to each year might be able to bring them in. “It’ll come to hummingbird feeders,” Tice explains. “You’re not going to get them in downtown Santa Fe or Tuscon, but if you have a summer cabin on the top of the Catalinas, they’ll come to your feeders.”

Here’s how to make a perfect batch of sugar water to feed hummingbirds.

Tice also says they’ll stop by native plants such as Indian paintbrush, penstemons, and agave.

Nesting Habits

Rivoli’s nesting habits mostly remain a mystery, but Tice is able to shine some light on the subject. “They don’t nest where they feed, and they tend to nest up in canyons in pine oak woodlands of the sky islands,” she says.

Find out everything you need to know about hummingbird nests.

Sounds

Listen for a short, clipped, high-pitched call that is repeated, sometimes in rapid succession.

Bird songs courtesy of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Rivoli’s Hummingbird Name Changes

If you think the Lucifer hummingbird has a wacky name, get ready for the weirdness surrounding the Rivoli’s. Originally, the Rivoli’s hummingbird was named to honor the second duke of Rivoli. In the 1980s, the Rivoli’s hummingbird became the magnificent hummingbird (and to be fair, they are pretty magnificent looking).

But then, in 2017, the change was reversed. Certain magnificent hummingbirds again became Rivoli’s, while others were newly dubbed Talamanca hummingbirds. The easiest way to tell whether you’re looking at a Rivoli’s or a Talamanca is to pull out a map. Rivoli’s call the United States through Nicaragua home, while Talamanca hummingbirds live in in Panama and Costa Rica.

Given that the American Ornithological Society is renaming all birds named after people, it’s likely the Rivoli’s hummingbird will get another new name in the near future.

About The Expert

- Vashti “Tice” Supplee is Audubon Southwest‘s Director of Bird Conservation. Throughout her career she has worked in research, habitat management, urban wildlife, and game management. At Audubon, she coordinates science-related activities with the National Audubon Society and serves as co-manager of the Arizona Important Bird Areas program.

Sources

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology: “Rivoli’s Hummingbird

- Tuscon Audubon: “Rivoli’s Hummingbird”

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.