Birds don’t require fancy designs when they’re choosing a nesting site. This simple DIY birdhouse is made from a single pine board and requires only a few tools to assemble. Learn how to build a birdhouse yourself and save your money for bird seed!

Birdhouse Materials:

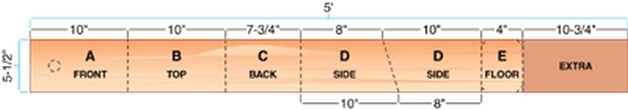

- One 5-foot 1- x 6-inch No. 2 pine board

- 1-5/8-inch galvanized deck screws

- 2-inch galvanized finishing nails

- Power drill

- Appropriate-size spade bit

- Hand saw

Step-By-Step Instructions:

Step 1

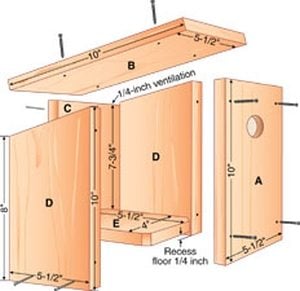

Using the full width of the 1-inch x 6-inch board, cut out the pieces as shown in the board layout diagram.

Step 2

Attach the front to the sides with 1-5/8-inch deck screws. Predrill the holes in the front piece to prevent the wood from splitting. After nesting season when it’s time to clean out the birdhouse, remove these screws for easy access.

Step 3

Attach the back to the sides with 2-inch finishing nails. Predrill the holes, making sure each one is straight.

Step 4

Cut about 1/2 inch off each corner of the floor for drainage.

Step 5

Recess the floor 1/4 inch up from the bottom of the house, then attach it with 2-inch finishing nails from the sides and back. Do not nail the floor from the front or you won’t be able to open it for cleaning.

Step 6

Attach the roof to the sides with 1-5/8-inch deck screws. That’s it! Next, learn how to build a bluebird house and attract nesting birds with better birdhouses.

The striking colors of birds aren’t just for our viewing pleasure. Every hue, stripe and spot serves a vital purpose. There two main reasons for their colorful bird feathers and markings. First, birds use their colors to attract mates and intimidate competition. And second, they use them to provide protection from predators.

When we look at birds, the colors we see aren’t always what they seem. Bird plumage colors are a result of either pigment or from the light reflecting off feathers. For example, bluebirds, indigo buntings and blue jays are not really blue. The color we see is the light reflecting off their brown feathers. Fortunately for the birds, some predators do not see the same bright-blue reflections as we do. So they remain protected. This is the same reason why a bluebird in heavy shade will not look blue.

When it comes to courtship, we know that it is the females of most species that select their mates, so the color and intensity of the male’s plumage can influence a female’s choice. Think about the northern cardinal. The male catches the eye of the female with his brilliant red color. She selects him as a mate, and her subtler tan and reddish coloring camouflages her when she’s nesting. Why, then, is the male not conspicuous to such predators as the sharp-shinned and Cooper’s hawks? Some scientists believe that hawks don’t see some red hues as well as female cardinals do. So the male’s flashy feathers may not stand out to hawks, but they still attract a mate.

Less colorful birds, such as sparrows, woodcocks, whip-poor-wills and sandpipers, are marked to blend in with their habitat. Their streaks, stripes, bars, spots and lines look so much like their surroundings that they are almost impossible for us to see. If you ever find the nest of a killdeer, meadowlark or mallard duck, you will know what I mean. They blend into their backgrounds perfectly. I remember flushing a whip-poor-will from her nest on a forest floor covered with dead leaves. Two days later, I returned to the site to photograph the bird on her nest, but I could not find her. It wasn’t until I stared directly at the bird for several minutes that her black eye popped out at me. I was shocked by how well it was camouflaged.

The brilliant colors some birds display during the nesting season tend to be muted when they molt into their fall and winter plumages. The bright yellow of a male American goldfinch, for example, becomes an olive-brown from late summer until the following spring. In fact, the goldfinches look so different in winter that many people believe they are a different species.

Bird plumage colors are definitely a science. Some might be brighter than others, but they all relate to their survival.

Plants have a lot more to offer than just beautiful flowers. Why not get the most out of your garden by growing plants to feed birds? Here, you’ll find 8 great blooms that offer seeds for birds.

Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia, Zones 3 to 9)

This is a garden classic birds adore. The traditional black-eyed Susan has dark centers and bright-yellow flowers, but now there are even more varieties to choose from. Grow in full sun to light shade for blooms in summer through autumn.

Blazing star (Liatris species, Zones 3 to 9)

Many gardeners know this plant as gayfeather. Don’t be surprised when you see an American goldfinch gripping the purple spikes of this flower head. It grows up to 5 feet in full to partial sun and blooms in summer.

Coreopsis (Coreopsis, hardiness varies by variety)

It’s not hard to find an annual or perennial coreopsis (also called tickseed) that will flourish in your yard. Plant in full sun and resist the urge to overwater, as it’s a drought-tolerant superstar that blooms in late spring through late summer.

Cosmos (Cosmos bipinnatus, annual)

With its gorgeous daisy-shaped blooms, this low-maintenance beauty seems too good to be true. Grow single or double blooms in full sun, and you’ll have flowers (and seeds to offer feathered friends) from summer through late fall.

Mexican sunflower (Tithonia rotundifolia, annual)

The vibrant, orange flower heads of Mexican sunflower will make a bold statement in any garden. Often mistaken for a zinnia, this sun- and heat-loving plant definitely holds its own when it comes to attracting birds.

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea, Zones 3 to 9)

Birds will feast on the cones of this backyard favorite. New varieties offer a wide range of colors, including purple, pink, white, yellow and orange. Plant in full sun for great results midsummer to early fall.

Purple majesty millet (Pennisetum glaucum ‘Purple Majesty’, annual)

It’s relatively new to the plant world, but birds have caught on fast! The plant itself is 4 to 5 feet tall, while the flower stalk offers another foot of delectable goodies for birds. Grow in sun or shade to get amazing foliage from spring to fall.

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus, annual)

You can’t expect to grow your own seed without this classic bird magnet. There are plenty of varieties to choose from, including cultivars that range from 2 to 15 feet tall and colors from yellow to red. Grow in full sun for summer and fall.

Safflower is easy to grow and the birds love it! Even if the birds don’t plant it for you, all you need to do is poke some kernels from your seed mix about an inch into the ground in spring. Safflower leaves get spiny as the plant matures. To save your fingers, grow the plant in a casual bed with blue larkspur, bachelor’s buttons, cosmos, marigolds and other easy-care, self-sowing annuals where it can take care of itself.

Even a small planting can keep cardinals, jays, chickadees, titmice, finches, native sparrows and doves investigating all fall and winter.

When it comes to attracting birds, there is a guaranteed recipe for success. Birds are attracted to a backyard that provides the tempting trio of food, shelter and nesting sites. And what’s a great way to offer all three? Conifers!

Seed-filled or berrylike cones offer food for birds like crossbills, while dense branches provide four-season refuge as a place to nest or hide from predators. Problem is, if your yard doesn’t already boast a few conifers, you may not have the space to grow a full-sized fir or large Colorado blue spruce.

That’s where dwarf conifers come in. These compact versions of the large trees offer beauty, versatility and the qualities that attract birds.

With sizes ranging from low-growing ground covers to small globe shapes to pyramidal trees growing 5 feet tall, small trees and shrubs easily fit into yards of all sizes. And, in addition to making your place more bird-friendly, their small stature and interesting colors and needle textures satisfy a broad range of landscape needs.

Small Trees That Attract Birds

While these small, or dwarf, trees are slower growing and smaller in stature than their full-size counterparts, the rate of growth and the ultimate height depend on your climate, site conditions and characteristics of the particular species.

Dwarf conifers offer a wide range of colors, shapes and textures, making them a great choice for scaled-down landscapes. Color options go beyond your typical shades of green to include yellows and oranges, soothing tones of blue, or variegated needles or scales.

Certain conifers even change color with the season—whether as contrasting shades of new spring growth, the fall foliage of deciduous conifers like larch, or the interesting plum color that appears with cooler weather on trees like false cypress and many juniper ground covers. Showy cone-like flowers on certain species of fir, spruce and pine provide spring color in hues of pink, purple, lavender and red.

The more diminutive varieties don’t provide much shelter for birds, though these ground covers can complement other plants or provide cones for feeding birds. The key is to select trees that serve birds, yet still fit the size and style of your landscape.

For shelter and nesting purposes, select trees with an upright or drooping growth habit. If you’re unsure how they’ll grow, check the plant information. There also may be clues in the tree’s botanical name. Upright cultivars often contain the words Fastigiata or Columnaris, while Pendular means it has drooping branches.

Small Evergreens for Feeding Birds

Small evergreen shrubs that grow in attractive mounds or are shaped like pyramids make great structural accents. Two examples are dwarf western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla ‘Thorsen’s Weeping’) and dwarf Sawara false cypress (Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Curly Tops’). Dwarf columnar species, such as common juniper (Juniperus communis ‘Compressa’) or eastern arborvitae (Thuja occidentalis ‘Degrott’s Spire’), provide intriguing exclamation points of interest in perennial beds or borders.

The selection of conifers for feeding birds is quite broad. The seed-filled cones of spruces, firs, pines and many others appeal to nuthatches, finches, grosbeaks, chickadees and other seed-eating birds. Junipers and yews provide a feast of berrylike cones for species like waxwings, robins, bluebirds and sparrows.

When and Where to Plant Trees

The best time to plant conifers is during the cool days of fall or anytime the ground is not frozen. Areas with milder climates can plant anytime from October through March. Most conifers grow best in slightly acidic soil in a sunny, well-drained site. Give the trees a bit of afternoon shade in the hot, southern regions of the country.

For the most part, yews (Taxus), hemlocks (Tsuga) and some species of false cypress (Chamaecyparis) also do well in partial shade. However, there are certain cultivars in nearly all conifer types that will tolerate some shade.

As a general rule, conifers also prefer moderately moist soil, though junipers, pines and true cedars (Cedrus) easily adapt to dry conditions once they are established.

Once planted, the trees don’t require much care. Soils of average or less fertility actually help encourage the dwarf characteristics, so applying a thin layer of organic mulch, such as compost, pine needles, shredded bark or leaves, once a year is plenty.

Love evergreens? Check out the types of Christmas trees you can grow.

Seven Best Small Trees with Benefits for Birds

These small trees may be dwarf in size, but they all provide giant benefits to birds in the way of seeded cones, insects and year-round shelter.

Creeping juniper

(Juniperus horizontalis ‘Mother Lode’)

Attractive ground cover with bright, golden-yellow foliage that turns plum in winter. Berrylike cones. Zones 3 to 9.

Dwarf Canadian hemlock

(Tsuga canadensis ‘Cole’s Prostrate’)

Low, spreading habit with cascading branches. Dense shelter for ground-feeding birds like towhees and juncos. Zones 4 to 8.

Dwarf Colorado spruce

(Picea pungens ‘Montgomery’)

Intensely blue, dense mound that becomes pyramidal to 5 feet tall when mature. Favored by chickadees and grosbeaks. Zones 3 to 8.

Dwarf mugo pine

(Pinus mugo ‘Slowmound’)

Dense, dark-green foliage, grows 3 to 5 feet tall and wide in 10 years. Zones 2 to 7.

Dwarf Korean fir

(Abies koreana ‘Starker’s Dwarf’)

Dwarf nest-form tree, grows 3 to 4 feet tall. Zones 4 to 6.

Golden eastern arborvitae

(Thuja occidentalis ‘Rheingold’)

Orangish-gold, globe-shaped tree with soft young foliage. Grows to 4 feet in 10 years. Zones 4 to 7.

Sawara false cypress

(Chamaecyparis pisifera ‘Curly Tops’)

Silvery-blue foliage with distinctive curled needles. Pyramidal habit, grows 5 to 8 feet tall. Zones 4 to 8.

Sunflower Seed: This is at the top of the list of all seed for feeding birds. If you want to rely on just one type of seed that is most attractive to the greatest number of backyard birds, hands down sunflower seed is the right pick in any form—in the shell (black oil or white striped) or medium cracked out-of-the-shell meats. All forms of sunflower seeds are relished by finches, chickadees, nuthatches, grosbeaks, cardinals, jays and even some species of woodpeckers.

There’s only one problem with sunflower seed—bully birds, such as blackbirds, European starlings and grackles, also love it, especially if it’s served in a tray feeder.

There’s a simple solution. Serve sunflower seeds from a feeder that allows only the smaller birds to enter the feeding chamber. These feeders are often called “exclusion feeders,” with smaller perches, weight mechanisms or fencing to keep the larger birds out.

Nyjer Seed (Thistle): If finches are your fancy, like the brilliant-yellow American goldfinches that frequent my area, then you’ll want to serve up this tiny black seed some people call thistle. It’s best served in a special tube feeder that has very tiny ports to keep the small seeds from pouring out.

Chickadees love nyjer seed, too, and their acrobatic behavior allows them to extract the seeds from the tiny food ports. It’s also a good choice if you’re overrun by larger bully birds. They have a problem feeding from the tiny ports.

Sugar Water: During spring and summer, sugar water mixed in the kitchen (one part sugar to four parts water, boil and cool before serving) is dynamite for feeding birds like hummingbirds and orioles. Because most hummingbird feeders are made of red plastic, and oriole feeders of orange plastic, the sugar water doesn’t even need to be colored to attract the birds’ attention. Once these desirable birds find the feeder, it will be a challenge keeping it filled.

Suet Cakes: One of my pet peeves is the commercial suet cake selection in bird stores. Most suet cakes contain a smorgasbord of foods other than suet, such as berries, oranges and even insects. The most common extra ingredient in suet cakes is birdseed. Birds that eat suet, including woodpeckers, nuthatches, chickadees and titmice, eat it to get the energy that the suet offers, so all the extras are virtually useless. If they require seeds, berries or insects, they’ll find those food items elsewhere.

For my backyard, I purchase only pure suet cakes.

Safflower Seeds: Though it may take some birds a little time to get acquainted with safflower seeds, cardinals, grosbeaks, mourning doves and house finches will frequent feeders serving it. Because northern cardinals prefer a flat surface to stand on when eating, a tray feeder or hopper feeder with a wide rim makes it easier for them to eat safflower seed. Even chickadees will remove a single safflower seed and fly to a nearby branch to crack it open.

Perhaps best of all, squirrels don’t like safflower seed! Consider switching to it if you’re pestered by these furry rascals.

Wild Birdseed Mixes: This is often the “mystery mix” you’ll find at grocery stores or on sale at the local discount store. It’s usually a mix of lots of millet, cracked corn and very few sunflower seeds. The basic problem with these feed-all mixes is that they’re not discriminating and may attract mostly undesirable birds and night critters, such as rats and raccoons. I recommend avoiding these do-all mixes, and stick with the specialty foods listed.

Feeding the most desired birds is probably much easier than you thought. Order off the right menu and you’re likely to see the birds you want feasting right outside your favorite picture window.

Feeders Hold More Than FoodThere’s more to filling feeders with the right seed to attract the birds you want. A feeder’s shape, placement in the yard and distance above the ground will determine what kinds of birds actually use it. And yes, proper cover and habitat play an equally important role.

Here’s a quick rundown of the most effective bird feeders:

Tray feeders, on a post or hanging, are open pantry shelves that attract most seed-eating birds. Problem is they also attract rain, snow and ice, so you have to maintain them more than other feeders.

Certain birds, such as cardinals, grosbeaks, bluebirds, woodpeckers and robins, will basically feed from only these types of feeders. Try to get one with screening or holes in the bottom for drainage to keep seed from spoiling.

Tube feeders are hanging cylinders with portholes and perches that are favored by small finches. Chickadees and nuthatches will use them, too.

If the bully birds figure out how to eat from a tube feeder, you may want to shorten the perches slightly, or enclose the feeder in a wire mesh that will allow only the little birds to get to the food. Commercially made exclusion feeders are available.

Hopper feeders, either on a post or hanging, are targeted to most kinds of seed-eating birds. They usually have an enclosed reservoir for seeds that slides food down to the open feeding tray below. The advantage is that the hopper keeps the seeds dry and always available to birds.

Suet feeders are usually small square laminated cages that hold blocks of suet. They can hang on a tree trunk or be suspended from a branch. They’re great for attracting woodpeckers, as well as titmice, chickadees and nuthatches.

Sugar-water feeders are for hummingbirds and orioles. Tanagers, finches and other birds may also use them. Simply keep them topped off with fresh homemade sugar water…and stand back.

It used to be that most backyard bird-watchers fed their visitors only in winter. Times have changed, though, and birders are starting to realize how much fun it is to feed birds year-round. To get more birds (and more kinds of birds) at your feeder, just follow these simple seasonal tips.

Feeding Birds in Winter

Not all birds head south in the winter. Lots of your favorites, like cardinals, chickadees, nuthatches and juncos, will stick with you through these cold, dark months and maybe even brighten your days a bit.

Birds flock to feeders in winter, especially during cold spells, heavy snows and ice storms. You’ll want to use large-capacity feeders so you don’t have to trudge through the snow as often to refill. Bring bird feeders up close to the house, since most of your viewing will happen from inside.

Keep those seed feeders filled with a mix of mostly sunflower and some white millet. Fill feeders in late afternoon so food is available just before nightfall and at daybreak, when birds need a boost after the long, cold night. Add an extra suet feeder to give woodpeckers and others another high-calorie dining spot.

Thistle is a winter must. Pine siskins, common winter visitors, love this seed.

Feeding Birds in Spring

Springtime is when birds are most active. A wide variety of colorful songbirds are coming home to nest, while others are just passing through, so pull out all the stops by offering a banquet.

For seed, using a mix of black-oil sunflower, white millet and sunflower chips (sunflower seeds without the shells) will cover most of your spring bases.

Chickadees, nuthatches, house finches and cardinals love sunflower, and so do migrating rose-breasted grosbeaks. The millet that falls to the ground might attract migrating white-throated, white-crowned and chipping sparrows. Sometimes even buntings show up at a feeder this time of year if it has some white millet.

Warblers and robins might eat the sunflower chips. Although these insect eaters can’t crack shells easily, they’ll eat chips. But by the time bugs become plentiful later in the spring, you probably won’t see many warblers, buntings or tanagers at your seed feeders.

Suet is a favorite of woodpeckers all year, but in the spring, tanagers, warblers, bluebirds and kinglets also relish this high-energy treat. Feed live mealworms to bug-loving new arrivals like bluebirds, robins, wrens, warblers and mockingbirds. It’s a nice high-protein snack.

Offering nectar in the spring beckons hummingbirds and even orioles. Here’s a spring must: Display fresh orange halves, meat side up, on a spike or dead tree branch. Orioles and tanagers can’t resist them.

Feeding Birds in Summer

Summer means lots of hungry young bills to feed, with some birds having as many as four or five broods of babies. Even though nature provides plenty of bugs, berries and seeds, it’s fun to watch fledglings flap their wings, squawk and beg their patient parents for food at your feeders.

Young and old birds alike will continue to eat your seed mix if it’s loaded with black-oil sunflower. Chickadees, house finches, sparrows, cardinals, nuthatches and more will bring their babies to your seed feeders for a lesson in finding a free lunch.

Suet eaters like woodpeckers are around all summer and love to bring the family over for a bite. Often, when you see several woodpeckers together at a suet feeder in the summer, you’re seeing parents teaching their big, awkward babies where to find a snack.

Both seed and suet eaters are attracted to seed cylinders if they’re heavy on sunflower and nuts. These large cylinders last a long time and need little maintenance, making them perfect when you’re away on vacation.

Goldfinches are sought after year-round but are only bright yellow in the summer. Feed fresh thistle (nyjer) all summer long to attract these beauties.

Summertime is hummer time, which means sugar water is a must. If you surround your feeder with honeysuckle, salvia or trumpet vine, you should see increased hummingbird action, especially in mid- to late summer as young ones join their parents at the feeder.

Feeding Birds in Autumn

Think of fall as spring migration in reverse, only with more birds, including young ones making their first trip south.

Feed a mix with sunflower, millet and chips to see some of the same migrants you saw last spring. Watch for white-crowned, white-throated and chipping sparrows as they move through.

Warblers and kinglets might join the year-round woodpeckers and nuthatches at your suet feeder. The arrival of the juncos every fall is the highlight of the season for many. Juncos stick around all winter and love to eat millet from the ground.

Orioles may make a pit stop at your jelly or nectar feeder as they head south. Hummingbird activity often peaks in September as local parents and babies join migrants from further north on the road to Mexico or Central America.

Year-round residents like cardinals, woodpeckers, nuthatches, jays and chickadees are hunkering down for the winter and are looking for regular sources of food and cover to get them through the cold months ahead.

Keep your seed and suet feeders filled so your yard becomes a regular stop on their feeding circuit. Make sure your seed feeder has enough space so larger birds like cardinals and grosbeaks are comfortable. A hopper feeder, tray feeder or tube feeder with a tray all work well.

You might consider adding a ground feeder this time of year, too. Also, freely toss seed mix loaded with millet on the ground in several places around your yard. Lots of juncos, migrating sparrows and towhees can spread out to eat with plenty of elbow room.

Bird Feeding Seasonal Checklist

WINTER

Chickadees, nuthatches, brown creepers, jays and woodpeckers all love peanut pieces. Add some to your seed mix, or hang a special peanut feeder to attract extra attention.

High-fat, high-calorie suet is the perfect food to help birds get through longer nights and colder temps. Don’t be afraid to place them right outside your

window for prime viewing (like this hairy woodpecker).

Put out a seed block, making sure it’s heavy on high- fat sunflower and nuts that birds love. Avoid seed balls with mostly millet and milo.

After the holidays, recycle your Christmas tree to give birds a convenient cover. You can also hang up seed ornaments and other treats.

SPRING

Don’t stop feeding the birds just because it’s warming up. Less natural food is available in early spring than at any other time of the year, since most berries and seeds from plants have been eaten throughout the winter and little growth has begun. It’s also too early for insects, so keep the food coming!

Starlings, grackles and squirrels can dominate feeders, so consider switching to safflower to break their habit since they don’t like it. Also focus on thistle for a while, bringing in beauties like goldfinches (above).

Fresh oranges lure orioles to your backyard and might even tempt tanagers, grosbeaks and house finches. Apple halves attract cardinals, mockingbirds, woodpeckers and others.

Many think of suet as a fall and winter treat, but it’s also a secret weapon for attracting spring migrants like warblers, tanagers and kinglets.

SUMMER

Make nectar for hummingbirds by mixing 4 parts water to 1 part white sugar. In hot weather, sugar water can ferment quickly, so change the nectar in your feeder at least twice a week. Don’t give up if you don’t attract them right away.

Thistle seed (nyjer) is definitely more expensive, but it’s a real treat for finches. Buy it in bulk and store in a cool, dry place.

Frequently replenish birdbath water during hot weather. Maintain a depth of no more than a couple of inches to allow birds to stand while bathing.

Bluebirds and robins love bugs. Try feeding live or roasted mealworms to entice these insect eaters.

FALL

Don’t take your sugar-water feeder down until late fall. No, it doesn’t interfere with hummingbird migration, and you just might get some stragglers.

Double the number of seed and suet feeders around your yard as birds are currently flocking, and there are more mouths to feed (like this black-billed magpie).

Switch to hopper-style feeders, which are more practical than tray feeders at times when the moisture from rain and snow can ruin food. Tube feeders work well in inclement weather, too.

Check the condition of your feeders and squirrel baffles to make sure they will make it through winter. Replace the ones you can’t repair.

When most people think of a bird’s nest, they probably imagine a grassy little bowl, held together with weed stalks and mud, in the crook of a tree. While this does describe the typical nest of an American robin, it doesn’t even come close for many other backyard birds.

Though nests all serve the same purpose-—to secure the eggs and young—the shape, depth, material and location vary greatly. Sizes range anywhere from a hummingbird’s golf-ball-size nest covered in lichens (pictured here) to a bald eagle’s giant platform of sticks, high in a treetop and sometimes weighing more than a ton.

Nearly every species has its own unique nesting habits. Take a look at some of the most fascinating nesters in the birding world.

Burrowing owl. Like foxes and woodchucks, some birds nest underground. But the burrowing owl just might be the most unusual. Most other owls nest in cavities, shelters or on the ground, but this flier actually digs its own 4- to 8-foot tunnel. It lays its eggs on the far end of the chamber. When the owlets are old enough to be curious, you can see their heads poking up at the entrance of a nesting burrow, looking around like kit foxes.

Belted kingfisher. Also an underground nester, the belted kingfisher digs its own burrow in the bare earth near the top of an exposed bank along a lake or river.

Chimney swift. Many birds make their own glue to hold their nests together. In China, a swift makes its entire nest from a gluelike substance it excretes from its bill. Here in North America, the chimney swift uses its gluey saliva to stick its nest to the inside of chimneys. Another common bird that glues its nest with mud is the barn swallow.

Common murre. Among the seabirds, the common murre will lay its eggs on the bare ledge of a sea cliff. The shape of the eggs offers natural protection: They’re long ovals with pointed ends, which makes them roll in a circle and not over the cliff.

American coot. A handful of waterbirds will build floating nests, creating small islands. The American coot typically constructs a cupped platform of cattails, rotted bulrushes or reeds, floating on 1 to 4 feet of water and attached to nearby aquatic plants.

Great horned owl. Like the peregrine falcon, the California condor and other raptors, this owl may construct a nest in a rock cavity or cave entrance on the face of a cliff.

Killdeer. Many birds build no nests at all. One of the best known of these is the killdeer, which lays four speckled eggs on gravel driveways, stony fields or walkways. When flushed off their eggs, the birds will feign a broken wing to distract the intruder from the eggs. Shortly after the eggs hatch, the chicks follow their parents away from the “nest.”

Baltimore oriole. Perhaps the most creative of all nest builders is the female Baltimore oriole. She weaves an intricate 8-inch pouch, attached to twigs high in an elm, maple or willow tree. With the entrance at the top, both parents feed the young by stretching downward into the pouch to reach the open mouths.

Atlantic puffin. This clown-faced shorebird prefers to nest under rocks along the coast of Maine and eastern Canada. (The black guillemot also nests like this.)

Cliff swallow. Though many birds use mud in their nests, only cliff swallows use tiny mud balls to construct globes, resembling adobe houses, attached to cliffs or the sides of buildings. You can find entire colonies nesting side by side in these mud condos.

Brown-headed cowbird. Often dubbed a “lazy bird,” this flier lays its eggs in another bird’s nest. Here’s the history behind the habit: When the bison roamed the great prairies, cowbirds followed the herd to eat the insects the animals attracted or disturbed. To keep up with the moving herd, they laid their eggs in the nests of birds that stayed in one place. As a result of this survival strategy, cowbirds never build their own nests nor raise their own young.

Whip-poor-will. Like its relatives, the whip-poor-will lays its two light-brown eggs on the dead leaves of a forest floor. It’s almost impossible to spot these eggs with the naked eye unless you flush the parent from the nest.

Marsh wren. This bird is also a weaver. Marsh wrens weave a sort of glove lashed to standing cattails, reeds or small bushes about 1 to 3 feet above the water. The entrance is on the side, and the inside is tiny compared to the outside dimensions.

Plover. Like terns, plovers lay their eggs on bare, sandy beaches, among seashells that look like the eggs. This helps protect them from the eyes of predators.

Bird Nesting Notes

Longest incubation period: Varies, though there’s a record of an albatross incubating its egg for 68 days.

Shortest incubation period: Though 12 to 14 days is normal for an American robin, one record shows only seven days before hatching. Hummingbirds require up to 16 days.

Most eggs: If an egg is removed from the nest of a domestic hen every day, she will lay another to replace it, up to 300 eggs a year. Northern flickers will do the same. One flicker laid 71 eggs in 73 days to replace the one egg removed each day.

Most eggs in a single season: Though northern bobwhites normally lay around 20 eggs in a single nest, as many as 40 have been found in one nest, probably laid by two or three hens. Bobwhites and wood ducks are among the few species that will “dump” their eggs in the nests of other hens of the same species.

Have you ever wondered how do cactus reproduce? Okay, maybe not. But, cacti, like many succulents reproduce by either seed or cuttings.

Believe it or not, cacti aren’t confined to the dry, desert areas of the U.S. They can be found growing in most states, like this one I photographed in upstate New York.

In nature, cacti often reproduce when segments or pads fall from the parent cactus and root where they touch the ground. The round pad, above, came from a Purple Prickly Pear (Opuntia bigelovii).

Why is a cactus covered in spines?

Another way that cacti reproduce is when animals brush by the cactus and a piece detaches and sticks to the animal’s fur. Later, it falls off, quite a distance away from the parent plant.

Pieces of cacti can survive for months without water, until there is enough rainfall for them to root into the soil, like this segment of Teddy Bear Cholla (Opuntia bigelovii).

Look for a cactus skeleton in the desert.

Often, you will find clusters of younger cacti that have taken root around the parent cactus when the segments fell and rooted like these Teddy Bear Cholla, pictured above. They may look fluffy and soft, like a teddy bear, but looks can be incredibly deceiving as many people have found who have reached out to touch one.

Check out cute cactus gifts for cactus lovers.

How to Propagate Cactus Plants From Cuttings

You can plant pads or segments of cacti and watch them grow. This is an easy way to take a single cactus and take cuttings of a pad and plant it.

While propagating cacti this way is easy to do, there are a few important steps to follow:

- Propagate cactus during the warm season, when the threat of frost is over.

- Make the cut at the joint where the segment attaches to the parent plant. For prickly pear cacti, you can cut a segment that consists of 1 to 3 pads.

- Place the new cutting in a dry, shady spot for 2 weeks to allow the cut site to ‘callus’, which protects the cacti from rot when it is replanted.

- Plant your new cactus in full sun with well-drained soil.

- Don’t water for a month after planting. Then water deeply, monthly until fall.

- Provide temporary shade for the first summer. You can do this by placing a plastic patio chair over the top or using shade cloth.

- Soon, you will begin to see new growth on your cactus.

Propagating cacti also comes in handy when your favorite cactus becomes too large or overgrown. Before removing it, cut a segment or two of the cactus and follow the steps above and replant them in the same spot. I have done this using some of my favorite species of Prickly Pear and Cholla with great results.

Next, discover 8 facts about Christmas cactus.

Succulents are by far, my favorite type of plants to grow. They have such interesting shapes and thrive despite my tendency to forget to water them. Succulents are not only beautiful, but are easy to grow. All you need are a few leaves. Getting started with growing succulents doesn’t cost much money. Ask your friend or neighbor if you can have a few leaves from their favorite succulent or purchase a small one from your favorite nursery. After that, growing succulents from cuttings is easy!

Learn how to grow and care for haworthia succulents.

To start, snip off a few leaves from your favorite succulent(s). You can also use stems; just remove the bottom leaves so you have at least an inch of stem.

Before planting, succulent cuttings need to ‘callus’ over where they were cut or else they can rot. This is done by placing the cut leaves on a paper towel and keeping them in an area with light shade for 4 – 5 days.

Next, fill your container with well-drained potting soil specially formulated for succulents/cacti. Don’t use regular potting soil because it will hold onto too much water that may cause your succulents to rot.

Plant your succulent leaves so that the soil is covering the bottom half of the leaf OR you can simply lay your leaf flat on the soil surface. Both ways will work for growing succulents.

Your newly planted succulent leaves will need to be watered regularly until they begin to root. However, it is important NOT to over water them. A good guideline is to water them using a spray bottle when the top of the soil dries out. A succulent grower described the perfect soil consistency as that of a “wrung out sponge”.

After planting, your succulent will start to root and grow new leaves in 6 – 7 weeks. Note: It is best to plant a few extra since not all of your succulent leaves may grow new roots.

Succulents that are easy to propagate from leaves include Crassula, Jade plants, Echeverias, Ice Plant, Jade Plant and Kalanchoe ‘Chocolate Soldier’. Succulents make great gifts – start growing succulents now and you will have some beautiful new plants for yourself and more giveaway as gifts in time for the holidays.

Psst—We’re hopping with excitement over this adorable bunny succulent.