Cooperative Behavior: How Birds Help Each Other

Updated: Mar. 26, 2024

Some types of birds work as a team for survival, nest building, and feeding. Learn more about cooperative bird behavior.

On This Page

Birds of a Feather Work Together

Avid bird-watchers probably notice that some birds are solitary, like the lone hawk perching along the highway. And some are social, like the goldfinches and cedar waxwings that flock to our gardens. We could say that their degree of social bird behavior is part of the personality of each species. But when birds gather, it isn’t just because they enjoy each other’s company. There are practical reasons that explain why some birds flock together and even work together.

Group Nest Building Bird Behavior

For a pair of birds to successfully raise young, building a nest is an important step. Unfortunately for many species, there’s no attempt at teamwork: Female robins, cardinals and hummingbirds all build nests with no help from their mates. Even the intricate woven nests of orioles are all the mothers’ doing.

But the news about the guys isn’t all bad. Some males—including red-eyed vireos, mourning doves, red-tailed hawks, bald eagles and great blue herons—bring building supplies like twigs, grasses and plant fibers for the female to shape into a nest. Among some wrens, the male builds the main structure and the female adds the nest lining.

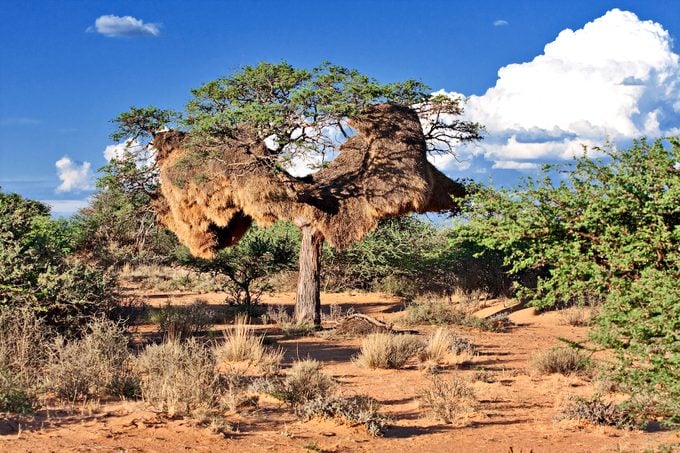

For one African bird, the sociable weaver, nest building is a task for an entire flock. A sociable weaver nest may look like a gigantic haystack draped over a short, sturdy tree. But up close, you can see dozens of small entrances on the underside, leading to individual nesting chambers. Sometimes more than a hundred pairs may help to build a single group nest—an almost unbelievable example of cooperative bird behavior.

Cooperating to Find Food

Even a flocking bird, when it comes time to eat, must look out for number one. But in some cases, birds will work together to find or catch their food. In the deserts of the Southwest, a family group of Harris’s hawks may hunt together. One or two swoop in to scare a rabbit out of a bush, while another waits to grab it as it dashes away. If their hunt is successful, the hawks will share the meal, with the dominant bird eating first and the others getting the leftovers.

Another fascinating example is the cooperative fishing of American white pelicans. These huge birds will line up side by side on the water and swim together toward the shore, dipping their bills in the water and driving fish ahead of them into the shallows, where they can be scooped up easily.

Winter Survival: Follow the Leader

Here’s a wintertime wonder you might see in any neighborhood with plenty of trees: a roving mixed flock of five or six kinds of birds making its way through the woods together. The leaders of the pack will be a flock of chickadees, flitting like acrobats in the outer twigs. Often there will be one or two nuthatches, a downy woodpecker and perhaps a brown creeper following along, clambering up tree trunks. A few titmice, a kinglet or two and sometimes a yellow-rumped warbler may join the flock.

These mixed flocks form because other birds like to follow chickadees around. Chickadees are active, alert birds, always on the lookout in every direction. They are quick to spot any hawk or other predator that comes near.

Birds like nuthatches or creepers, moving along with their faces next to tree bark, may be less likely to notice the approach of danger. But they can simply listen to the chickadees and fly to safety when the usual chatter of the little birds turns to alarm calls.

Learn about another fascinating bird behavior: caching food.

Bird Mobbing Behavior

The concept of safety in numbers gets cranked up another notch when birds engage in mobbing behavior. If songbirds discover an owl roosting in the daytime, they gather around and badger it with alarm calls, sometimes flying at it and even pecking at the back of its head.

Small predators like screech-owls are usually mobbed by small songbirds. Big ones like great horned owls are more likely to be mobbed by crows or other larger birds. The owls are seldom driven away by this harassment, so it might seem that the mobbing behavior doesn’t work. But it does mean that all the birds in the neighborhood know the owl’s location, so they won’t be taken by surprise.

Bird mating behavior: who’s the boss?

Sharing Child Care Duties as a Flock

If you ever watch a nesting pair of American crows, you might get the impression that more than just two adults are bringing food to the young birds in the nest. And you’d be right. Pairs of crows very often have assistants, usually their own offspring from previous years, bringing food and helping to guard the nest. Some crow nests have five or more helpers in addition to the parents. The same kinds of helpers have been observed in many other species, from purple gallinules to western bluebirds.

Some birds take group nesting behavior to an even higher level. Among the groove-billed ani, an odd tropical cuckoo that gets as far north as Texas, up to four pairs of adults cooperate to build one big nest, where all the females lay their eggs. All the adults in the group help with incubating the eggs and feeding the young.

The ultimate example of cooperative bird behavior may be the acorn woodpecker. In western oak woods, these gaudy birds live in colonies of a dozen or more. One, two or three females may lay eggs in a single nest; after the eggs hatch, all the adults in the group feed the young birds. But the woodpeckers don’t cooperate just at nesting. They also work as a group every fall to harvest acorns and store them in dead trees riddled with holes, saving up enough food to help the flock live through the winter.

Watch Birds to Observe Their Behavior

These are just a few examples of the ways birds can work together. If you watch carefully, you may discover something new about the birds right outside your window. Even the most common of them can still surprise us with their bird behavior.

Why Trust Us

For nearly 30 years, Birds & Blooms, a Trusted Media Brand, has been inspiring readers to have a lifelong love of birding, gardening and nature. We are the #1 bird and garden magazine in North America and a trusted online resource for over 15 million outdoor enthusiasts annually. Our library of thousands of informative articles and how-tos has been written by trusted journalists and fact-checked by bird and garden experts for accuracy. In addition to our staff of experienced gardeners and bird-watchers, we hire individuals who have years of education and hands-on experience with birding, bird feeding, gardening, butterflies, bugs and more. Learn more about Birds & Blooms, our field editor program, and our submission guidelines.